PORTFOLIO

Pictured above, in a natural element that always leaves enough negative space for a pithy block of text to be overlayed when his photograph appears unbidden on someone's screen, is the writer Walé Oyéjidé. Walé is many things to many people. He is an acclaimed designer, a regretful lawyer, a musician, and a savant when holding a ladle full of fried plantains. Above all, he is a story-teller.

In his writing, Walé draws on his experiences as a designer, an attorney and a global citizen. He is adept at tapping into the concerns that face uncelebrated populations, and conveying those issues in a manner that is widely digestible but still authentic to the original subjects. He believes that words written for a wide audience do not need to be any less clever, any less urgent or any less true, simply because of the large scope of the prospectives readership. It is his goal to tell human stories broadly, without losing sight of the magical details that make us who we are.

P R O S E

The following passages were written for different campaigns by the brand Ikiré Jones,

to convey its ethos of cultural inclusion and global acceptance.

BEFORE THERE WERE GUARDED FENCES THAT STRETCHED ACROSS THE ENDLESS DUSK.

Before there were state issued documents that determined which endangered children were worthy of being saved. Before fear and ignorance became the currency with which we bought and sold our precious lives. There were indigenous women that marched with crops stretched across their shoulders and infant arms draped across their necks. There were men whose histories would be brushed away like footprints, while newcomers claimed to settle the lands where their ancestors had once walked. And there were stateless people who understood the worth of welcoming strangers into the warmth of their homes.

Perhaps there are those among us that don't remember. Perhaps there are those among us for whom it is more convenient to forget. But for those of us who came against our will, and those of us who later fought our way over because we too wanted to dream, the memory is ever present. And we are here to serve as a reminder.

Although the promises of the past may not have been made with us in mind, we fully intend to hold them to account. Regardless of what tongues we speak. Regardless of what names we choose to call in prayer. Regardless of what offense it might cause to the delicate sensibilities of the old guard.

We are the America that is here to stay.

***

SOME OF THEM PACKED WHAT LITTLE THEY HAD, AND STRODE ACROSS A distant DESERT.

Some of them abandoned established careers and respected titles to sit at the bottom rungs of a foreign society. Some climbed fences. Many boarded planes. But all of them came from far away to live in a place where they would be mocked if they weren't ignored. Of course, they did it all for us.

We are that tomorrow that was claimed by brave women and men who had little, but risked it all because they believed. We are those children that were born between borders. Influenced by a new world, and inspired by the old one they left behind. We carry our parents dreams with us; like ghosts that no one can look past. There are no tables we will not overturn, and there are no locked doors we will not dislodge.

We are the children of engineers that drove your taxis. We are the sons of surgeons that served your tables, and we are the daughters of diplomats that held open your elevator doors. In spite of their genius, our parents were bedeviled by the black magic of bureaucracy and backward immigration policies. But not us.

We are the future that their hard-work and discarded dreams foresaw.

***

DID YOU RECLINE COMFORTABLY IN YOUR BEACH CHAIRS, AND GAZE OUT INTO THE HORIZON, AS OUR CHILDREN WASHED UP ON YOUR SHORES?

Did you sneer at your newspaper headlines over a warm breakfast, and curse your strange new neighbors, as the media whispered that we were the ones to fear? Or did you take our hands and pull us from the waters, before asking us for the stories that dragged us so far away from the people that we loved?

We are sons and brothers, just as you are. We've held hopes, and abandoned dreams, just as you have. And like you, we have sworn to persevere. So that we can one day provide for the families that we left behind. There is pride, even in the depths of our unspoken suffering. There is elegance, even in the way we carry burdens that would bury most men. And there is determination, nestled in the quiet knowledge that we will not be defined by the horrors that have befallen us.

From the bellies of crowded cargo ships. From the teetering edges of toppling rafts. And from the jaws of hungry seas that threatened to swallow us every inch of the way. We traveled across the world to seek asylum.

Our hands may have been empty when we arrived, but our hearts will always be full.

***

Speculative fiction

The following passages were written to combat negative tropes about the African continent

by recasting real African cities and neighborhoods in futuristic settings.

Nairobi 2081AD.

"In the beginning, the drones were used to hunt poachers. Imported technology intended to stop the export and extinction of important wild-life. Motorcycle-sized mosquitoes buzzing mechanically between the tree-tops with decimal-point accuracy and a thirst for blood. Their efficiency would have been admirable had it not been accomplished with such calculated zeal. The hungry hum of in-flight havoc blending with our hymns became a common harmony. Roaming door to door to bear uninvited witness, these unmanned guests seemed increasingly inhumane as their algorithm-driven eyes looked into the faces of men; unable to recognize the souls emanating behind our eye-lids.

What occurred next should have been no surprise to us. Still, when their hovering shadows careened through our village streets like sentient storm clouds seeking an escape from the sun; when pillars of smoke spontaneously erupted from the ground where children had stood moments before; and when we lifted our spears to take aim at skies that no longer sheltered us; it was then we realized we'd been sitting idly as unseen hands steered us toward our end.

No one remembers which of us was the first to climb atop the cooling metal carcass of a downed flyer, but the story of a lone Masai stepping into a screaming death's flight-plan would travel like an air borne outbreak. An epidemic pouring through Africa's porous borders; indiscriminately infecting all it touched with the hope of freedom. Soon, silhouettes of dark skinned sons in brightly hued robes could be seen rising with weapons and shields aloft in the Nairobi sun.

The end was near, but it would not be ours."

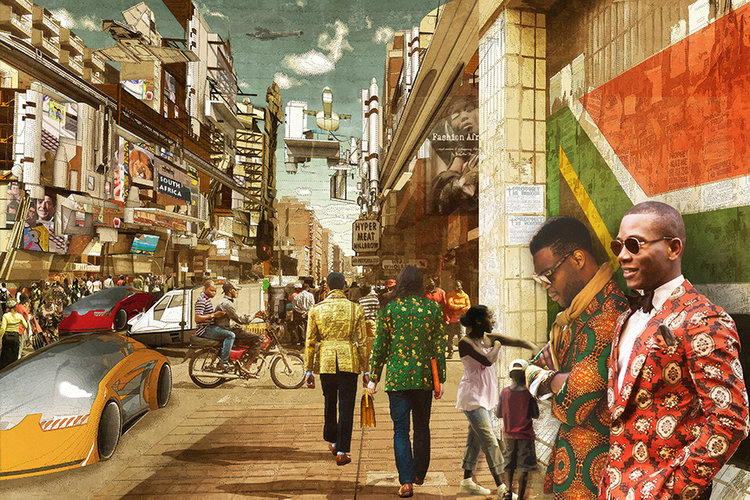

JOHANNESBURG 2081 A.D.

"Men like us once made our living on our knees. Crawling through the bowels of illegal gold mines that hid the threat of a death in the dark abyss behind every corner. In moments when groups of rival migrant miners ambushed us for our spoils, it seemed like we were at odds with the entire world above us. For weeks on end, we lived by candle-light. Scraping at the earth with the fear that we might never again see the skies or loved-ones that had forgotten us. We were the sort of fathers that became shadows. Leaving behind ghost memories of tucking our sons into bed. Phantoms of evening embraces with wives whose faces we now struggled to remember in the dark.

Things changed slowly at first. More of us began to emerge from the blackness below with increasingly large hauls of gold. And then we found it. Gleaming, immeasurable and all ours for the taking. We returned to Johannesburg as different men. The kind of men whose hands had become calloused from clutching at ancient treasures, and were now strong enough to mold the future."

narratives

The following passages are fictional first-person accounts

written from the perspectives of different individuals in African society.

Memoirs of an Internet Scam enthusiast.

Our fathers' generation was deluded into thinking it knew hard work because those men had to brave a lifetime in the fields while their hands bled, and their backs wilted in the oppressive Nigerian heat. But they never had to face the burden of conjuring a barrage of blissfully deceitful emails to hundreds of gullible Western retirees before lunch.

This was work for men with nothing to lose. Because we had nothing to start with in the first place. Nothing but the dreams we invented for a living, and the collection of lives we would leave in shambles after ransacking their inboxes, savings and stock portfolios with the keys that they had given us to their own homes. Each of us was Shakespeare & Sheharazad. A thousand yarns to spin around the necks of a thousand fools who would be strung along for a thousand nights at the cost of thousands of dollars.

Every morning I waited. For the moment of divine inspiration which would guide me to the end of a new Master Work that would eloquently begin: "Dear Sir, It is a pleasure to meet you. Please let me tell you of a great financial opportunity that involves my sweet cousin Muyiwa and a wire transfer from your account..."

Memoirs of an Asylum Seeker.

Life at home quietly embraced then smothered us, like the hands of a 19th century alleyway strangler emerging from an English fog. Amidst peers who promised well-pointed AK-47s were more profitable than piddling about on a pitch, I held my dreams of being a footballer aloft. For some reason or the other, all of us sought an escape from an estranged country that entangled us because it knew no other way to love.

Like too-many others, I paid what portion of a king's ransom an Eritrean pauper could dredge together, and climbed aboard a Libyan fishing boat aimed toward the Mediterranean Sea. All of us had heard of the barges that didn't make it across. The bodies that littered the bottom like deep sea sculptures molded by someone who had only seen terror. We thought that things would be different. That if we held each other tightly and stared at nothing but the horizon, it would eventually draw us ashore like some accelerated Darwin illustration inspired by a geopolitical nightmare called "Today". Less than a mile off the coast of Lampedusa, the boat's engine stopped. Mass panic ensued. As the edges of the barge began to tip into the water, we realized that we had been wrong.

longform fiction

The following passages are excerpts from a longer manuscript.

The Collector

Despite his career-long presence in the periphery of violence, my father was loath to raise his fists against anyone in our new country. His turn away from the brute negotiation techniques that had once brought him notoriety as a Nigerian Intelligence Officer was not because his fellow Americans were any less worthy of an occasional bludgeoning, but because he did not want his status as an exiled coup plotter hiding among immigrant taxi drivers to be prematurely revealed. So, while we sat in front of a collection of old African statues that had been exhumed from the attic of deceased missionary, it came as a surprise when my father suddenly stood up in the middle of a museum auction to walk across the room and whisper into the ear of a retired ethnography professor that had been out-bidding him all evening. There was a short, quiet, exchange. Then the professor put his hand down. “Sold,” the auctioneer exclaimed a few moments later, as the professor nervously wiped his glasses before hurrying out of the room. “One Lot of pre-colonial Igbo masks,” the auctioneer continued. “To the dapper gentleman from Nigeria!”

“What did you say to him—the other bidder?” I asked my father. While absently flipping through the evening’s brochure to find his next conquest, he responded: “I told him how many of our people had to die for these statues to arrive in this elegant museum. And then I asked him what his feelings were on the concept of proportionality.”

You see--my father had become a collector.

Like yours, my people have some familiarity with the affairs of an auction block. In the 19th century, men and women bearing my resemblance stared ahead defiantly while customers examined their teeth and sought to negotiate the bills of sale that had been hung around their necks. Seeing no better alternative, some other ancestors helped affix irons around the necks of their neighbors while considering themselves fortunate to be able to return to their homes. There were those that remained free of the slave trade’s grasp, but in other ways, they too suffered an unwelcome acquaintance with the colonial chattel industry. The experience of watching one’s family being split apart and sold to discerning buyers is an unspeakable horror. But to a lesser degree, so is the experience of seeing one’s culture being sold piece-by-piece to the highest hand of a foreign bidder. As my people learned, some of history’s most prodigious distributors of human misery were also the most prolific collector’s of stolen art.

Among his many misdeeds, the great emperor Napoleon is known for looting the four bronze Horses of Saint Mark’s Basilica during his conquest of Italy. The horses had stood triumphantly outside the basilica for six centuries before being taken by the French in 1797. When Napoleon’s troops tore through the city of Venice, they also tore timeless masterworks from the frames in which they had been hung. At the peak of the Napoleonic Wars, French soldiers could be seen strolling through the streets with the remains of priceless oil paintings slung over their shoulders. On those evenings, the helpless Venetians watching this take place grieved for more than the sacked city that smoldered around them. They grieved also for the brushstrokes that they would never see again.

Later, German soldiers with imperialist ideals would also prove to be avid patrons of the arts. Because it was not enough to crush the human spirit by herding thousands of civilians into concentration camps, the Nazis also stole paintings and artifacts from private homes, museums and temples all over Europe. Afterward, buildings, books and sculptures that did not meet their critical standards were razed to the ground. As they were in all things, Hitler’s followers were ruthlessly organized. Government sanctioned looting agencies sought out cultural works that had been itemized on lists of prized items to be seized for the Fuhrer’s collections. On more than one occasion, quiet meals in small Jewish homes were interrupted when large groups of soldiers stormed into the dining rooms to demand a rumored masterpiece be produced. Several decades later, irreplaceable pieces of art would still be found in the dusty attics of forgotten war criminals that had lived to become loving grandparents.

Regrettable as these acts of piracy were, they pale when compared with the unbridled looting of West Africa’s treasures. The theft of European art throughout the ages has been widely recognized as unjust. And where possible, stolen items have been returned to their rightful nations of origin. Whereas, the plunder of African art has barely been acknowledged outside the continent. Masterworks made of brass and clay move quietly from one private European collection to the next. Little mention is made of their pedigree, and nothing is said of their mysterious journeys from a distant continent. To do so would be to peer under the slave-woven carpets that hide the many atrocities upon which this world of Western comfort was built.

In the 1990s, the small New York City apartment of a nurse and taxi-driver was not the ideal place to house a priceless collection of African art. In its confines, we kept all of the luxuries that one would expect of a newly immigrated family. There was a small television with a metal antenna that mirrored the mapping of distant constellations, a worn mantle-piece that held salvaged pictures of once-regal people who ruled in better times, and above the couch there was a large Nigerian flag that my mother occasionally ironed while sighing with regret. I should have known it was just the beginning when I woke one morning to find a wooden pair of Yoruba Ibeji figures on the coffee table. It wasn’t unusual for my father to come home from his long drives with something curious in his trunk. The people of New York discarded all sorts of things on their street corners—old furniture, neglected loved ones, and occasionally forgotten antiques from a different world. The two identical Ibeji figures had tribal marked cheeks, beaded necklaces, and skirts made from straw. If you had seen triumph and suffering in your life, you could be assured when looking at their miniature faces that they had seen more. Sculptures like this had inspired the work of Pablo Picasso, and had even brought him to speak against the colonialist tendencies of some of Europe’s most beloved nations. But more importantly, for centuries, sculptures like this had inspired people of West African descent to persevere. On the cracked coffee table of a working class Nigerian family in New York, the figures only stood a few inches tall. But whenever I looked at them, I felt a hundred feet taller.

At home, when we were part of the upper class, my parents had never cared much for cultural trinkets that recalled our primitive past. Growing up, it had been my impression that in Nigeria, the less Nigerian one pretended to be, the more sophisticated he would seem to everyone else. But half a world away, without the thick accents and aromas of home surrounding us, the two small sculptures in our living room felt like a long awaited reminder of the beauty from which we had come.

Sensing a way to reclaim his previous identity, my father became compelled to collect more artwork from his homeland. He began by scouring the backs of discount stores. But soon, he made a weekly habit of infiltrating antique auction houses after pressing the suit he had been wearing during our escape. There were few things that could surprise the fellow residents of our project building. The youngest of our neighbors had seen slashed bodies with outstretched feet that prevented the elevator doors from closing. They had seen disasters on the scale of Gomorrah outside their doorways, with no policemen in sight. But before my father’s obsession came to fruition, they had never seen a middle-aged man cursing in Yoruba while trying to push a six-foot Malian sculpture up a narrow staircase.

Over the years, our home became increasingly crowded. One couldn’t cross a room without staring into the eyes of a mask from Benin, or without narrowly avoiding being impaled by the spear of a statue from Ife. Every facet of African culture was on display. And when viewed in its grand scope, no one with vision would have called any of it primitive or unworthy of pride. Still, it was an overbearing space to live in, and his collecting never stopped. For months, I wondered why my mother didn’t put an end to Baba’s madness. Later, I came to understand that she appreciated something about my father, and our people, that I did not.

Slowly, the stabbings in our building’s elevators abated. Outside, the commerce of crack in the courtyard came to an end. Things became different in the sort of ways that populations without artisanal coffee shops rarely experience. Eventually, there was only a respectful silence and the long pilgrimage of visitors that queued around an unremarkable project building in Bedford Stuyvesant, Brooklyn. From far and wide, people of all shades came to visit The Collector. But there was a special significance for those whose forefathers had come to this land while shackled in the bowels of unregistered boats. For them, it was perhaps the closest they would feel to finally coming home

her Reluctant Wardrobe

We ask too much of the women who care for us. We do so with rigid-unwritten customs bolstered by the weight of a thousand years. We do so with stone-inscribed roles carried down from distant mountaintops by overly serious men who have been endorsed by God or by the State. And we do so while listening sympathetically with an impotent ear that claims to understand, but refuses to do anything differently because this is all that we have ever known. We ask much of these women. Not least of which are the implicit demands that they bury who they are, that they forget who they one day hoped to become and that they do it all without complaint, because there are the ever-present needs of others to consider. We ask these things because we know that they love us. And because we know that they will not refuse. We ask these things because we always have.

My mother’s uniform was a shapeless and inoffensive pair of scrubs. To some, these clothes were a symbol of pride, an outward representation of care and service. But not to her. My mother wore them with resentment. Years before, on a different part of the globe, she had worked hard enough to ensure that she would never have to wear a pair of scrubs again. This new world was one that, by all rights, was supposed to be long behind her. Yet, there she was every day. At work with downcast eyes and a barricaded tongue, as she took orders from uncertain physicians who were born a generation after she earned a license to practice and eventually teach medicine in her country.

Unfortunately, there are few things that a brilliant career trajectory and a reputation as a gifted musician can do to appease a mob of military assassins with plans to draw their annual salary bonus from whatever heirlooms are hidden inside your home. When she fled with her husband and child to a foreign country under the guise of a new name, my mother also left most of what she was behind. “It’s all still there,” she would sometimes say. “It’s all in our house, waiting for us to come back.” Somewhere in that smoldering building that no one would ever call “home“ again, the fragments of a ground breaking doctoral thesis lay unrecognizable in the ashes. Various diplomas curled up softly at the edges as their glass frames crunched under the boots of soldiers and scavengers who would periodically ransack the property. Souvenirs procured by my mother while giving lectures around the world were torn from their cases and distributed among the soldiers’ wives-of-the-day. With my 11-year old hand in hers, my mother had ducked under the spinning blades of a helicopter that would carry us to safety. As we ran, a duffel bag she was carrying fell on the helipad and was torn open. A hundred photos flew out of her favorite album. Birthdays, weddings and award ceremonies. All of those memories were pulled into the vortex of the helicopter’ spinning blades and thrown over the sides of a tall roof. As we rose above the city, she knew then that there would be no past for us her to hold on to. On the many nights when she would feel abandoned and alone, there would only be the present to contend with.

Unlike everything else in her well-ordered life, my mother’s scrubs lived in a crumpled mass at the bottom of her small closet. Every evening, they would be sequestered in the dark; victims of her tiny attempt to momentarily discard the life in which she was now unjustly imprisoned. It was a temporary escape, until the morning. But above the wrinkled work clothes, perfectly pressed on matching cedar hangers, hung the few salvaged dresses of a now-disgraced statesman’s wife. And there they would wait, exalted and perfectly preserved, even if hell itself came. Until the day my mother returned home.

In addition to the branding and copy authored for Ikiré Jones,

Walé Oyéjidé's writings have been published in legal journals and in Litro, a literary magazine.